You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Faith’ category.

I remember watching a girl, maybe 5 years old at the time, climbing high on play equipment at the local park. When her face was a few feet higher up than mine as I stood and watched, but still a few feet below the top of the climbing structure, she grew uncertain and looked at her mother for advice. Her mother said, “Listen to what you tummy tells you. If your tummy tells you it’s too high, you can come back down again.

I was at once impressed with this piece of advice, and also concerned. I don’t remember being encouraged to listen to my gut when I was a child, so I’ve been learning to trust my gut as an adult. Not an easy task. In that respect, I really appreciated the gift this mother was giving her child. At the same time I was concerned for the child. As we reach for new skills, abilities, and experiences, and try out new areas in life, isn’t it natural to feel fear in the pit of our stomachs? Is it good to follow the guidance of our feelings then?

Is there a general answer to that question? I suspect not. Still, since we as Quakers claim our faith to be based on the authority of God speaking within us, we would do well to have a way to ensure that we aren’t confusing our feelings with an authoritative message straight from God.

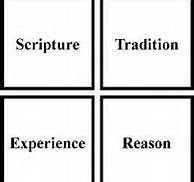

I am a big fan of the Methodist quadrilateral, which was articulated in about 1954, but founded on John Wesley’s 17th century theology and church-building. The quadrilateral lays out four sources of authority for Christians. In Wesley’s mindset, these four sources were supposed to thought of as a fourlegged stool, which of course would be wobbly if the four legs weren’t balanced. In seeking to settle a theological point, conflicting advice, or perplexing choices, we should consider the Bible, tradition (or the cumulative wisdom of the church), our own experience of God, and the learning we have gained through our intellectual reasoning. Like early Quakers, Wesley believed that God does make the truth known to each and every one of us. Truth is not hidden from our sight, or revealed only through certain special people, such as priests or mystics. Each of these sources is considered authoritative, and the four should be expected to be confirm one another if they are truly representing God’s truth.

I find this tool helpful in conceptualizing how different churches and Christians can all be reasonable, faithful people, considering the same sources of information and still arrive at different conclusions – with integrity – on matters such as gay marriage, women in spiritual leadership, Middle East peace, and any number of other thorny issues.

I should also say that the quadrilateral helps me understand differences between churches. Methodists may seek perfect balance perfectly between these four sources of authority, but other don’t seem to do that. The Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches appear to me to put far greater emphasis on “tradition” than the other quadrants. That is their charism, for good and bad. Protestants tend to emphasize Scripture more strongly than the other three.

What about Quakers? I’ll be interested to hear what others think. My conclusion is that we as Quakers operate with a three-legged stool of authoritative, reliable sources of knowledge of God: Scripture, experience, and tradition.

Based on my reading of Robert Barclay’s Apology, I don’t think early Quakers considered reason to be authoritative. Considering reason to be authoritative was very popular in the 1600s. In those heady early Enlightenment days, many hoped and believed that our reason was given us by God, and that reasoning as a gift of God represented God’s essence and would lead us back to its source: God, who is Truth. Robert Barclay, though he hadn’t encountered Freud’s analysis, tells us that while reason can bring us into an understanding of God’s mind, we humans are also prone to using our reason to justify our own ideas and flights of fancy. Hence, Barclay concludes, reason is not an authority. Instead it is neutral. It is as likely to lead us to the right conclusion as to the wrong conclusion.

Quakers, with our emphasis on “inward, unmediated revelation” probably emphasize experience more than other denominations do as a source of authoritative knowledge of God.

Scripture? Our faith group split over how authoritative scripture is, so there may not be a unified understanding of the role of Scripture in Quaker theology.

Tradition? Quakers – in general – place a great deal of trust in practices of making decisions, clearness committees, the business meeting, and early Quaker texts. I would say tradition is considered authoritative, though the different branches might differ some on how much weight to attribute to tradition and scripture if the two appeared to be pointing in different directions. We don’t rate tradition as highly as the Roman Catholics do, who attribute ultimate authority to tradition, as represented by the Pope.

Emotion? Is there a Quaker response to a child who feels fear in the pit of her stomach as she climbs high? “Trust your gut!” or “Keep climbing, even if you are a little scared at first.” Further reflections in Part II.

Query for prayerful reflection: When have your emotions revealed God’s truth to you? When have your emotions obscured God’s truth from your sight?

Once again, QuakerQuaker is the medium for an important Quaker conversation. Quaker Pagan has a lovingly crafted an appreciation of liberal Quakerism’s openness to the work of the Spirit in its many forms. The blog post contains a plea about use of language, “Christian Friends must be particularly careful when they speak of Jesus, or when they speak from the Bible.” Thankfully, Quaker Pagan doesn’t hold different standards for different Friends. She suggests that all Friends should be “bold and low”, bold in speaking what the Spirit reveals, and humble in not making claims broader than the Spirit’s message.

Jim Wilson has a response on QuakerQuaker, and the comments to both blog posts are well worth reading. I very much appreciate Quaker Pagan’s care, concern, and careful wording. She makes her request as graciously and kindly as I think anyone could. And yet…

Those of you who know me will be aware that I didn’t come to my Christian faith easily. Until I was in my 20s, I considered Christianity to be a tool used by the powerful to justify oppression of the vulnerable. Apartheid-era South Africa was the place where I saw this dynamic in action most vividly, growing up as I did in neighboring Botswana. I didn’t gain the freedom to consider a relationship with God until I encountered South African liberation theology in the late 80s. From Black evangelical Christians in South Africa, I learned that the Bible in fact tells the story of God standing with the oppressed, and in the mind of these South Africans, Christianity is best summarized in Galatians 5:1: “It is for freedom Christ has set us free. Stand firm then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery.”

Since then, I have continued on my spiritual journey of learning where God is in the midst of suffering. As an anti-apartheid activist initially, then a spiritual director with homeless persons (many of them working on becoming sober), and now a hospital chaplain, my spiritual compulsion is still to learn about God and suffering. There is much pain, despair, anguish, fear, tears, and feeling overwhelmed, of course. Nonetheless, I continue to be amazed when I see how often people who face oppression, addiction, illness, death, and grief talk about a God who empowers, gives joy in unexpected places, comforts, and permeates everything and breaks forth in the world with generosity, love, and spiritual abundance. The predominant theme of Christianity, as I continue to learn it, is freedom.

We Quakers tend to be quite aware of the ills of the world, the injustices, the wounds, the hurts, and we often express our outrage at the inequalities in the world, and take care not to offend. One of the things I appreciate most about Quakerism is the attention we give to this earthly life, not just the hereafter. I am an activist at heart, and I agree with the bumper sticker that says, “If you aren’t outraged, you aren’t paying attention.” But precisely because there is so much injustice, pain, and war in the world, I think we need our Quaker Meetings to provide reminders of resilience, model generosity, and above all, to reassure each other that even when all seems dark and hopeless, God is not asleep, but is active in the world “working all things together for good”. I think we need reminders, even when things seem hopeless, that God still gives us complete spiritual freedom to act with love. No matter how desperate our circumstances, we always have the choice of being in right relationship with God, and uniting with God and humans in “those things that are eternal”. We are free now, and will know even greater freedom when we unite with God after death.

Sadly, I don’t encounter as much of this spirit of freedom and abundance in Liberal Meetings as I would like. There are the troubles of the world, of course. Also, there are so many among us who have been emotionally and spiritually wounded, and in response, we thoughtfully choose our words about God with care and caution lest we offend. It is good to be concerned about offending other, of course. In his letter to the Romans, Paul is very clear that our freedom should not come at the expense of others, and we must have concern for how our actions affect our brothers and sisters. We do not have the freedom to do and say things that harm, offend, embarrass, diminish, or confuse another person. And yet we need fearless, bold, and joyful abandon so we can freely speak about our experience of God, yes, even if we sound foolish in worldly terms.

I am concerned that in this environment, Quaker Pagan’s encouragement of caution and concern will further dampen our already-too-timid talk about God. Rather than guarding our words carefully, at this time, I think we need greater emphasis on freedom to shout and sing and dance to proclaim God’s presence in our midst, yes, especially in the midst of tragedy and despair.

The way I’d like to see us balance the concerns for freedom and compassion is in to err on the side of generosity. I would like us to remind ourselves that, provided we all are mindful of the power of words to hurt, we generously encourage each other to speak freely about our experience of God. I’d like to see us all claim responsibility for our own feelings, recognizing that in community, we will almost certainly be hurt at times, and cause pain to others, no matter how hard we’re all trying to avoid it. I’d like to see us commit to lovingly speak with any person who causes us pain, and commit to use the freedom to speak to that person about the effect of his/her words, educate if needed, and forgive or ask forgiveness as appropriate.

I’d love to hear you speak freely about your experience of the Divine!

Query for prayerful consideration:

How has God been present to you in difficult times?

In my previous blog post I said that, according to early Quakers, statements about the subservient role of women, slaves etc only apply to those living under the old covenants. Then Jesus came, and he fulfilled the law and embodied the New Covenant, ending the need for written rules and blood sacrifices. Under the new dispensation, humans need no intermediaries between us and God, and God speaks directly into our hearts to tell us what we are supposed to do, and all humans are equal in this ability to hear and obey God. Complete freedom and equality, in other words, for the faithful.

Then I asked what, if anything, we need to do/say/believe in order to take part in the freedoms of the new Covenant, and I wondered what we should make of people who aren’t part of the New Covenant.

Some caveats first: The answers I have arrived at are probably not very original, but this is the first time I have worked my way to them myself. I suspect some of you will not be happy with the answers I have arrived at. I’m actually not very happy with them myself. They fly in the face of some of my previously held beliefs. However, my task is not to find answers that easily fit with previous categories. If they did, I would have to suspect myself of trying to make God fit my world view. My answers, though they don’t make me happy, are more trustworthy to me because they aren’t what I would have expected. They are the result of my attempts to be faithful.

Many Christians, especially those of the evangelical persuasion, say that it is belief in Jesus Christ that makes us beneficiaries of the new covenant. Those Christians point to texts like John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” As I engaged with these texts during the past week, I discovered that most of them are in the book of John. In Acts and Romans it also often says that belief “saves”. I don’t dismiss those texts, but I don’t think they are about the covenant. Rather, they are about the life-giving joy of believing. (Look for another blog post later on what belief does.)

So I took a look to see if “belief” is tied to “covenant” elsewhere in the Bible. By far the greatest number of references to covenant is in the Old Testament, as you would expect. Here’s the main text reference in Jeremiah 31:33: “This is the covenant I will make with them after that time, says the Lord. I will put my laws in their hearts, and I will write them on their minds.” The interesting thing is that this way of talking about covenant doesn’t change when we move into the New Testament: In Hebrews 12:2, Jesus is called the “perfecter of faith” and the covenant is compared to a will (a gift).

In all of these passages, God or Jesus are the initiators, the ones with agency, and humans are simply passive recipients. Humans aren’t required to do anything for the covenant to happen.

When requirements are listed – for the most part separated from covenant – it sounds like this: In Hebrews 10:36, it says “You need to persevere so that when you have done the will of God, you will receive what he has promised.” Hebrews 13:15-16: “Through Jesus, therefore, let us continually offer to God a sacrifice of praise—the fruit of lips that openly profess his name. And do not forget to do good and to share with others, for with such sacrifices God is pleased.” It is also made clear that we are not supposed to insult or mock or make light of the Divine. Again, actions are required, not beliefs.

Then I tried turning it around to see what the Bible says about beliefs or faith. When the concepts are first brought up it is in the Old Testament, of course. It is rarely, if ever, in connection with the Messiah. Later, when Jesus does show up, the belief/faith concepts don’t seem to change meaning from the way they were used in the Old Testament. Even in Hebrews 11:1-2, the main text that describes covenant, faith is defined as follows: “Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see. This is what the ancients were commended for.” The rest of the chapter lays out what these “ancients” did, not what they believed in. When discussing “faith”, it seems like even the new testament mostly means it not in the sense of belief in Jesus, but in the sense of commitment to God and doing good. “Being faithful” actually seems like a much more apt phrase than “belief” does in its modern use. The requirement is to be faithful, then, not to hold a particular set of beliefs about Jesus.

All of this goes a long way towards answering the question of what the New Covenant means for people who don’t believe in Jesus. The way I read it, God initiated the covenant and Jesus perfects it. It makes no difference whether we believe or not. All humans are beneficiaries. Hebrews 10 goes to great lengths, in fact, to persuade us that Jesus’ sacrifice was a one-time event and it has already been accomplished. There is nothing any one of us can do or say at this point that could undo the event, it has been done “once for all.”

And yet there is this notion that Paul dispenses rules to people who live under the Old Covenant. Can there be people into whose hearts and minds God hasn’t (yet?) put the law? People who “just don’t get it” – who won’t persevere, praise, share, encourage others to do their best, be respectful of the holy, etc? Perhaps such people need some instructions spelled out. Without inner guidance from the heart, having written laws may be more helpful and effective. Or perhaps “the people who live under the Law” are all of us – perhaps we are free in some areas but still live “under the Law” in others? Or could it be that some of us, for whatever reason, haven’t claimed the freedoms of the new covenant that have been given? Galatians 5:1 creates the idea that freedom must not just be given, but also claimed: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery.”

Queries for prayerful reflection: What does the New Covenant mean to you?

Friends tend to say that although we don’t practice the sacraments outwardly, we do practice them inwardly or spiritually. Hence we can talk about communion as an experience of unity with God or with other worshipers. Spiritually, we might call it baptism every time we dedicate our lives to God or when we are called to speak in Meeting and are filled with the Holy Spirit speaking through us.

Quakers tend to keep our discussion to the two Protestant sacraments, but there are of course five additional sacraments practised by Roman Catholics: confirmation, confession, marriage, holy orders, and the anointing of the sick. Most Christians agree that the sacraments, whether 2, 4, 5 or 7 in number, are things that Jesus told his followers to do, outwardly or inwardly, whether or not we agree what exactly the spiritual reality is intended to be.

So… what about foot washing?

Jesus’ act of washing his disciples’ feet is described in John 13:1-17. The disciple Simon Peter initially doesn’t want Jesus to wash his feet, but Jesus replies, “Unless I wash you, you have no part of me”. After washing everyone’s feet (including Judas’) Jesus says, “Now that I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also should wash one another’s feet. I have set you an example that you should do as I have done for you. I tell you the truth, no servant is greater than his master, nor is a messenger greater than the one who sent him. Now that you know these things, you will be blessed if you do them.” The words that he uses after washing his disciples’ feet are very similar to the words Jesus used after sharing a cup of wine and breaking some bread with his disciples.

When theologians try to explain why foot washing shouldn’t be a sacrament, they variously claim that Jesus uses “as” in this passage, not “like”, or that this passage doesn’t contain words that are evocative of covenant but that the wine/bread and baptism passages do. However, linguistic analyses aren’t terribly persuasive to this Quaker. My method of Biblical interpretation involves asking the ultimate source of authority, “the spirit that gave forth the scriptures” in George Fox’s words, and then asking my Friends to help with my discernment.

I was fortunate to spend some time in 1993 in community with people from the Church of the Brethren, where they practice foot washing at Easter every year. Brethren and Mennonites not only practice foot washing before sharing communion (they call it Love Feast), but also require their members to be reconciled with God and with their community members before participating in foot washing. The theology is of servanthood and humility: all Christians are expected to serve others and be willing to humble themselves.

I’m not sure how reconciliation came to be a condition for participating in foot washing. Perhaps because reconciliation may require us to be willing to humble ourselves, either by asking forgiveness or by letting go of “righteous anger”? Or maybe it’s because Matthew 5:23-24 says, “…if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there… First go and be reconciled to them; then come and offer your gift.” Maybe this is the one time of year when Brethren and Mennonites decide to ritualize the event?

Experientially, reconciling before foot washing makes sense to me. Before I participated in foot washing, I tried to imagine what it would be like to kneel at the feet of someone with whom I was in conflict, and wash their feet. It was hard to envisage it because the symbolism of kneeling is so strong. It was harder still, though, to imagine that same person kneeling down before me and washing my feet. Foot washing is such an intimate act that I don’t think I could give my feet over to someone whom I don’t trust. It is hard to imagine how pride could survive a foot washing ceremony.

In fact, this image has become one of my spiritual tests whenever I am ill at ease with someone or feel tension or possible conflict. In worship, I create a little guided imagery for myself and see if I can live into a scenario where I wash their feet and they wash mine. If the imagery makes me too uncomfortable, one way or the other, I know I have to take steps to address the situation or improve the relationship.

Foot washing seems to me to be an outward expression of an inner state of humility, willing vulnerability, and reconciliation. These spiritual states seem crucial to God’s vision for the human condition. And therefore I do believe that foot washing should be as important, spiritually, as baptism and communion.

Queries for prayerful consideration:

Have you participated in a foot washing ceremony? What was the inward experience that accompanied the outward event?

As a child growing up in Botswana in the early 70s, I knew that White people like myself were bad. Not that anyone ever said such a thing, but living in the shadow of apartheid South Africa as we did, it didn’t need to be said. For two of my school years, I was one of two White children in a school of 500. I was painfully aware of my unnatural skin color, and the hardest part was the assumptions I thought people were making about Whites like me: rich, superior, lacking concern for those less well off. I wished I could wear a sign that said “I’m not like that!”

With God’s help, I was eventually able to embrace myself as a White person. Painful as my identity issues were, I came to be grateful for them. That’s where my passion for justice was born. My search for a place where I belonged led me into the arms of a Loving God.

Yesterday I startled myself by telling my husband that I’m considering converting to Islam. Really, I am?

Now, my natural instinct after growing up in Botswana has always been to be interested in other cultures, religions and beliefs. After September 11, 2001, I decided to educate myself about Islam and the Qu’ran, and I liked what I found. I like the focus on doing one’s duty, submitting to God ritually in prayer, the importance of charity, modest dress, the habit of expressing gratitude, and acknowledging the uncertainty of life. In recent weeks, I’ve delved more deeply into Islam because of an interfaith event I’m planning at the hospital, and yesterday I watched numerous interviews with Yusuf Islam, formerly known as Cat Stevens, in which he talked about his conversion to Islam.

And then I found myself saying I want to convert to Islam. Really?

Kinda. But no, not really.

No, I don’t want to convert to Islam. What I want is to wear a “hijab”, a Muslim head covering.

Just like when I was a kid in Botswana and wanted to wear a sign that declared my belief in the equal worth of all human beings and my compassion for those who suffer, I feel the need now to distance myself from those who “accuse” Obama of being a Muslim, not being born in Hawai’i, those who protest against the social center/mosque near “Ground Zero”, plan to burn the Qu’ran, etc. Sadly, many of these shameful utterances are portrayed as natural expressions of Christian faith.

I don’t think it’s wrong to be a Christian, any more than I think it’s wrong to be White, but I feel a strong need to express my Christian love and my belief that all humans are of equal value. What better way to do that than by wearing a hijab?

Query for prayerful consideration:

What does Love require of you when a group with which you identify does things that are abhorrent to you?

My faith has been challenged again this past week. I had dinner with a dear friend of mine last Sunday, whose 15 year old son almost died in August last year when an ice cave collaped on him and a friend. The two boys were buried under the ice for over 4 hours before they were rescued. For most of that time, the rescuers and my friend C didn’t think the boys could have survived. Last Sunday, C told me that there was a point when her son had been under the ice for about three hours when she had a sudden image of God standing over her son with a knife in hand, just like Abraham stood over Isaac, and God asked C: “Are you ready to give your son to me?” C says that, stricken with fear, she nonetheless answered, “Yes, Lord, if you give me the strength to live without him.”

Just a few minutes later, the rescuers heard a voice under the ice, her son’s voice, and he was rescued. His friend was rescued a little while later.

I have always resisted theologies that portray someone’s illness or death as “God’s will” or part of “God’s plan”. As a chaplain I witness the suffering that people go through when someone they love dies, especially when that someone is their child. I can’t bring myself to believe that God would ever be the cause of that kind of pain.

And yet I could hear in my friend’s story that she found comfort in giving her precious son to God. As painful as it was, it was profoundly meaningful and it helped her face a future without her son.

I’m not sure I am explaining this very well, but I can’t think of what other words to add.

In my own life, I know that I am a much better parent when I think of my daughters not as mine, but as beloved children of God, who have been entrusted to my care. When I think of the incredible gift they are in my life, and that I am accountable to God for raising them to be loving, responsible, and independent women – that’s when I make the best decisions on their behalf. I am a much better wife when I think of my husband not as mine, but as a child of God, and when I remember that one of my major responsibilities as a wife is to help him grow closer to God.

My friend C says that after she turned her son over to God, she was filled with gratitude for the 14 years she had had with him.

I still find it hard to think of “God’s will” when a child dies. What I do know is that I am deeply grateful for the people who have appeared in my life and whom I have been fortunate to love and nurture. I hope that my gratitude will always sustain me, even when it is time to say a last “goodbye” to someone I love and give him or her to God.

Queries for prayerful reflection:

What does it mean to give someone to God? In what ways do I turn the ones I love over to God? In which ways do I not turn them over to God?

I arrived late, so I may have missed it. It is possible the presenters talked about it and I just didn’t arrive in time to hear it. But I don’t think so, because the Quaker presenters on building peace talked about how easily peacemakers can become discouraged and then they led us into an activity designed to generate hope and joy. The source to which they led us to find joy and hope was our own accomplishments.

Sigh. I could get discouraged.

Friends, I agree that we often do wonderful things. And the presenters to whom I am referring gave a good presentation, and I found myself stirred to join in their efforts at the Air Force base an hour or so down the road – after spending an hour by myself in the woods to re-find my hope and joy following their presentation. So there is lots of good stuff happening. I do not wish to complain. And yet I have to ask, what happened to the joy of faith?

When I look back at my blogging and other writing and speaking during the past 6 months, I discover that I have started preaching. Me – preaching? I feel like I owe my liberal friends an apology: “Honestly, I swear, I didn’t mean to become a preacher of the joy I find in God. It just … happened.”

But seriously, here is the anatomy of my transformation to becoming a preacher of the Good News of faith in God:

The first movement was God lifting me out of the deep trough of depression in 1994. I had been passively suicidal for months following the end of an abusive relationship. And suddenly, after daring to yell angrily at God in a private prayer time, God filled me with love. I began to know the power of God for good, and I began to talk about God as our source of hope, just a little bit. But I still looked to prophetic, righteous anger as our source of energy for transforming the world.

The second movement was attending worship at West Hills Quaker church whenever I was in Portland to visit my in-laws. I had Ffriends there from my seminary days. What I noticed was how little time attenders at the church spent expressing righteous anger over the shortcomings of the world around them and how much time they spent doing things like cooking meals together for homeless people.

The next step was in the days after September 11, 2001, when mental health counselors suggested that we limit our intake of bad news. In the run-up to the Iraq invasion in 2003, when depression began to set in again at the hopelessness of everything, I heeded their advice for the first time. I took a few weeks off from intense reading of newspapers and only took in enough to be informed about the big picture. To my amazement, I found an upsurge of energy to be engaged in resisting the war!

At some point after becoming a Good News Associate in the summer of 2003, I noticed how joyful I usually feel after being with my fellow Associates, most of them evangelical Quakers, and how joyless liberal Quakers often seem to be.

While teaching Ignatian spirituality last fall to men and women in recovery from addictions, many of whom are homeless and have lost their jobs and family relationships as a result of their substance abuse, I noticed that many of them nonetheless expressed gratitude, time and time again. They were grateful for things like waking up in the morning; for being free from the dehumanizing effects of their addictions; for God’s love; for the kindness others showed them. Their gratitude stood in stark contrast to the fears, worries, and cautious planning I would hear at Quaker Meeting from all those of us who have houses, food, and family life.

My next step was a simple decision to be more joyful. I felt embarrassed to be spending time worrying and fretting about the stuff in my life when women and men who have nothing can be so grateful, generous, and compassionate. It was clearer to me than ever before that joy does not arise out of having a sufficiency – if that were the case, homeless people would be unhappy and liberal Quakers would be happy. My AHA! was that joy comes from entrusting one’s future to God. So yes, it is as easy as deciding to be joyful.

So, Friends, I decided to be joyful. I prayed to God that I would feel gratitude for all the amazingly wonderful things and people that surround me. I prayed that my worries and sadness about the problems of the world would simply fade away. I decided to tell people about my discoveries, and my early blog entries (look at October, November,and December entries) give more details about my journey to joy. It began to feel burdensome to listen to comfortably-off people worry and be sad.

Since deciding to be grateful, I keep discovering more and more reasons to be joyful. It is no longer merely a decision now. More and more, I feel it rising up within me. I still work in a hospital where I see death and illness, and I still work with homeless men and women whose material futures seem bleak, and I still read of conflict and troubles in the world. Suffering is still real. What’s different is that I now know hope and joy are not waiting for us on the other side of attaining world peace, eliminating physical pain, or eradicating poverty. Peace of mind is not waiting for us on the other side of securing the future for our children or securing work or our own retirement. Hope is not based on seeing the exact route to the happy ending at the end of the story. Trust in the future is not based on seeing the societal developments that will lead to a peaceful settlement between conflicting sides.

I can no longer keep myself from telling everyone who wants to listen that hope, joy, peace, and feeling safe arise out of being in the hands of a God who promises to be with us in whatever we encounter. How can I keep from proclaiming what I know to be true – that this God of ours has plans of peace for us? That God is actively at work, using even the bad things that happen for good.

The mystery of it all is that as I allow this joy and gratitude to bubble up within me, I can hardly keep myself from throwing myself into work for peace and justice. The more I trust God, the more I also see God at work in societal developments, too. It looks like peace, abundance, and safety are just waiting to be birthed into the world, and I want to be part of it!

Query for prayerful consideration:

What is the source of hope in my life?

The last time I saw my Norwegian grandfather, Bestefar, alive I had a big argument with him. He criticized someone I love, and as a passionate 18-year old, I rose to the defense of that someone. Bestefar and I exchanged harsh words and parted in anger.

About a week later, the call came from my grandmother, Bestemor, telling us that Bestefar was in the hospital and she thought he might not survive. My mother and I ran to the car and drove the 25 miles to the hospital. I loved my Bestefar and wanted him to live. If he was going to die, I desperately wanted a chance to make things right again between us first!

Bestemor was standing outside the hospital when we arrived so she could be the one to break the news to us: Bestefar died. Then she took me aside and told me that before he died he had said that he loved me and and had no hard feelings about anything. It was such a relief to know that he had forgiven me, and that relief made my sadness over his death more bearable. My heart and mind have sought out the sweetness of that relief many a time.

Many years later, as a hospital chaplain, I learned enough about what happens when people die from massive heart attacks to suspect that Bestefar wasn’t able to say anything at all before he died. In fact, I am quite certain that Bestemor made up those “dying words” in order to spare me the pain and regret over arguing with Bestefar the last time I saw him alive.

And yet the sweet relief of forgiveness is just as strong in my heart and mind as it was before I knew. In true Quaker style, I have the experiential confirmation from my own life of the Truth told in the Bible about the mystery of God’s forgiveness of humans and what was accomplished by Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

It is truly a mystery to me that, even now that I know that Bestemor was probably saying something that was untrue, I still know in the depths of my being that he would have forgiven me if given the chance – because that is the kind of man he was. And I know even more deeply how much Bestemor must have loved me and cared about me in order to tell that lie – she who had been a stubborn truth-teller all her life, no matter what the cost to herself. In her wisdom, she knew I might be tormented with the ‘if only”s that so often plague the bereaved, and so she gave it, even though it wasn’t really hers to give.

I was forgiven and loved because of who THEY were, my Bestefar and Bestemor, not because of who I am or anything I did.

Whenever I try to explain the how and the why of this situation, I fail. It makes no sense to me. But it has Truth written all over it. And perhaps precisely because it makes no logical sense that I would feel forgiven by Bestefar, this experience tells the larger Truth about God’s forgiveness? Perhaps they are – in fact – the same story? God’s love and forgiveness are above, below, around, and within our human failings and efforts at reconciling.

In the language of soul, I know that we are all loved and forgiven by God, and Jesus’ death and resurrection are the reason. Because of who THEY are, not because of who you and I are or anything we did to deserve it.

Don’t ask me to explain, because I can’t.

Query for prayerful consideration:

In the language of the soul, how have I come to know God’s love and forgiveness?