You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Discernment’ category.

I remember watching a girl, maybe 5 years old at the time, climbing high on play equipment at the local park. When her face was a few feet higher up than mine as I stood and watched, but still a few feet below the top of the climbing structure, she grew uncertain and looked at her mother for advice. Her mother said, “Listen to what you tummy tells you. If your tummy tells you it’s too high, you can come back down again.

I was at once impressed with this piece of advice, and also concerned. I don’t remember being encouraged to listen to my gut when I was a child, so I’ve been learning to trust my gut as an adult. Not an easy task. In that respect, I really appreciated the gift this mother was giving her child. At the same time I was concerned for the child. As we reach for new skills, abilities, and experiences, and try out new areas in life, isn’t it natural to feel fear in the pit of our stomachs? Is it good to follow the guidance of our feelings then?

Is there a general answer to that question? I suspect not. Still, since we as Quakers claim our faith to be based on the authority of God speaking within us, we would do well to have a way to ensure that we aren’t confusing our feelings with an authoritative message straight from God.

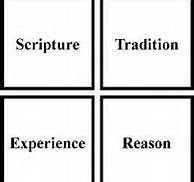

I am a big fan of the Methodist quadrilateral, which was articulated in about 1954, but founded on John Wesley’s 17th century theology and church-building. The quadrilateral lays out four sources of authority for Christians. In Wesley’s mindset, these four sources were supposed to thought of as a fourlegged stool, which of course would be wobbly if the four legs weren’t balanced. In seeking to settle a theological point, conflicting advice, or perplexing choices, we should consider the Bible, tradition (or the cumulative wisdom of the church), our own experience of God, and the learning we have gained through our intellectual reasoning. Like early Quakers, Wesley believed that God does make the truth known to each and every one of us. Truth is not hidden from our sight, or revealed only through certain special people, such as priests or mystics. Each of these sources is considered authoritative, and the four should be expected to be confirm one another if they are truly representing God’s truth.

I find this tool helpful in conceptualizing how different churches and Christians can all be reasonable, faithful people, considering the same sources of information and still arrive at different conclusions – with integrity – on matters such as gay marriage, women in spiritual leadership, Middle East peace, and any number of other thorny issues.

I should also say that the quadrilateral helps me understand differences between churches. Methodists may seek perfect balance perfectly between these four sources of authority, but other don’t seem to do that. The Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches appear to me to put far greater emphasis on “tradition” than the other quadrants. That is their charism, for good and bad. Protestants tend to emphasize Scripture more strongly than the other three.

What about Quakers? I’ll be interested to hear what others think. My conclusion is that we as Quakers operate with a three-legged stool of authoritative, reliable sources of knowledge of God: Scripture, experience, and tradition.

Based on my reading of Robert Barclay’s Apology, I don’t think early Quakers considered reason to be authoritative. Considering reason to be authoritative was very popular in the 1600s. In those heady early Enlightenment days, many hoped and believed that our reason was given us by God, and that reasoning as a gift of God represented God’s essence and would lead us back to its source: God, who is Truth. Robert Barclay, though he hadn’t encountered Freud’s analysis, tells us that while reason can bring us into an understanding of God’s mind, we humans are also prone to using our reason to justify our own ideas and flights of fancy. Hence, Barclay concludes, reason is not an authority. Instead it is neutral. It is as likely to lead us to the right conclusion as to the wrong conclusion.

Quakers, with our emphasis on “inward, unmediated revelation” probably emphasize experience more than other denominations do as a source of authoritative knowledge of God.

Scripture? Our faith group split over how authoritative scripture is, so there may not be a unified understanding of the role of Scripture in Quaker theology.

Tradition? Quakers – in general – place a great deal of trust in practices of making decisions, clearness committees, the business meeting, and early Quaker texts. I would say tradition is considered authoritative, though the different branches might differ some on how much weight to attribute to tradition and scripture if the two appeared to be pointing in different directions. We don’t rate tradition as highly as the Roman Catholics do, who attribute ultimate authority to tradition, as represented by the Pope.

Emotion? Is there a Quaker response to a child who feels fear in the pit of her stomach as she climbs high? “Trust your gut!” or “Keep climbing, even if you are a little scared at first.” Further reflections in Part II.

Query for prayerful reflection: When have your emotions revealed God’s truth to you? When have your emotions obscured God’s truth from your sight?